Article 2 Section 2 of the Constitution

The President shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur.

Article 1 Section 1 of the Constitution

No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation; grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal; coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts, or grant any Title ...

About Treaties

The United States Constitution provides that the president "shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur" (Article II, section 2). Treaties are binding agreements between nations and become part of international law. Treaties to which the United States is a party also have the force of federal legislation, forming part of what the Constitution calls ''the supreme Law of the Land.''

The Senate does not ratify treaties. Following consideration by the Committee on Foreign Relations, the Senate either approves or rejects a resolution of ratification. If the resolution passes, then ratification takes place when the instruments of ratification are formally exchanged between the United States and the foreign power(s).

The Senate has considered and approved for ratification all but a small number of treaties negotiated by the president and his representatives. In some cases, when Senate leadership believed a treaty lacked sufficient support for approval, the Senate simply did not vote on the treaty and it was eventually withdrawn by the president. Since pending treaties are not required to be resubmitted at the beginning of each new Congress, they may remain under consideration by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee for an extended period of time.

In recent decades, presidents have frequently entered the United States into international agreements without the advice and consent of the Senate. These are called "executive agreements." Though not brought before the Senate for approval, executive agreements (and Treaties) are still binding on the parties under international law.

Why is SCOTUS arguing States vs the Sovereign Nation of the Navajo when The Supreme Law of the Land makes this an International Court Issue?

Justices appear divided over Navajo Nation’s water rights

By Matthew L.M. Fletcher

on Mar 21, 2023 at 2:13 pm

FacebookLinkedInTwitterEmailPrintFriendlyShare

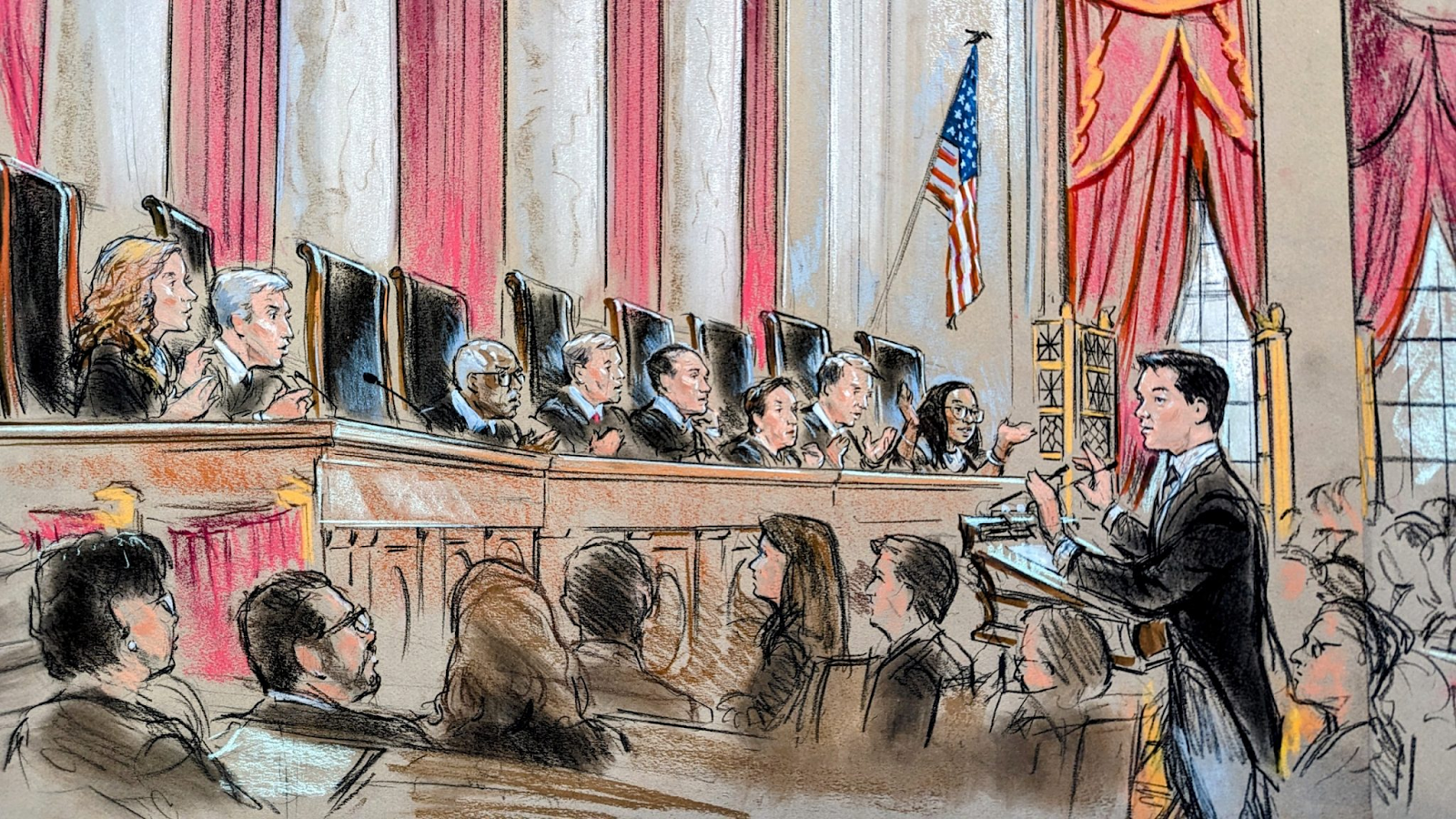

Sketch of man in a dark, long suit arguing before the justices. Justice Sotomayor's chair sits empty.

Frederick Liu, assistant to the solicitor general, argues for the United States. (William Hennessy)

What water the United States owes the Navajo Nation under the 1868 Treaty of Bosque Redondo formed the crux of the argument in Arizona v. Navajo Nation. The treaty, known by the Navajo people as the Naal Tsoos Sani, or the Old Paper, established the Navajo Reservation as a “permanent home” for the Nation. The justices on Monday wrestled with the scope of the government’s responsibility to ensure that the reserved land has enough water.

More than a century ago, the Supreme Court held in Winters v. United States that treaties establishing Indian reservations should be construed to include a right to enough water to establish a homeland. More recently, the court in United States v. Jicarilla Apache Nation held that a tribal nation suing the federal government for breach of trust must point to contract or treaty language explicitly establishing a right. These two precedents have come into conflict here.

The Supreme Court seemed evenly split at oral argument on Monday. Justices leaning toward the federal government and three western states worried that the Navajo Nation’s request for relief would upset the current allocation of the Colorado River water as the effects of a generation-long drought are being felt. Justices leaning toward the Nation pointed to the federal government’s assumption of control over tribal water rights as establishing an enforceable right. Justice Amy Coney Barrett seemed to be the deciding vote.

Attempting to avoid the default interpretative rules of Indian treaty construction, which strongly favor the Nation, Assistant to the Solicitor General Frederick Liu framed the issue as a matter of property, turning to the popular “bundle of sticks” theory of American property law. In the federal government’s view, the establishment of the Navajo Reservation created a bundle of property rights belonging to the Navajo Nation, including Winters rights. But, Liu said, the rights guaranteed under the treaty end there. From the government’s perspective, once the property rights are established, the Navajos are just like any other water user in the west. Even if there is not enough water, the United States has no obligation to provide water.

Sketch of man in glasses arguing at the podium.

Shay Dvoretzky argues for the Navajo Nation. (William Hennessy)

Justice Neil Gorsuch probed this theory, asking whether the United States could dam the Little Colorado River and stop all river water from reaching the reservation. Liu agreed that the United States could not affirmatively deny the Navajo Nation any water, but would not budge from the position that the government has no duty to affirmatively act to make water available.

Justice Elena Kagan framed the issue differently. If a treaty is a contract in which the United States promised a homeland to the Nation, she asked, then why wouldn’t the federal government, as a party to the contract, have an enforceable obligation to ensure that there would be enough water? The government’s answer seems to be that an Article III court does not have the power to order the government to comply with such a contract term.

In that case, Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked whether the trust obligation of the treaty was simply meaningless. She suggested that, if it is, the Nation agreed to a contract in which it gave up vast lands and resources in exchange for a much smaller reservation and nothing else.

Barrett asked about the difference between a breach of trust and a breach of contract in the Indian treaty context — in other words, should the justices rely on Winters or Jicarilla? Liu first seemed to agree that there was a difference between the two types of lawsuits. But when Barrett suggested that under a breach-of-contract claim the expectations of the parties would become relevant, especially those of the Navajo Nation because Indian treaties are construed to the benefit of tribal nations, Liu resisted. He then argued that the Nation’s expectations under the treaty effectively were irrelevant, asking the court to import the “Jicarilla standard” that requires courts to focus exclusively on the understanding of the federal government. To do so would make the canons of construing Indian treaties moot in this suit.

Arguing for the Navajo Nation, Shay Dvoretzky attempted to focus the court on the federal government’s actions over the years to show that the government acknowledged a fiduciary duty. Several justices asked about the significance of the federal government’s successful opposition in the 1950s to the Navajo Nation’s motion to intervene in Arizona v. Colorado. If the government objected then, Gorsuch asked, would it object again? The United States refused to take a position on whether it would do so now. Dvoretzky argued that the government’s successful objection to the Nation’s previous motion to intervene created a “Catch-22” because even if the Nation intervened now, the Supreme Court could simply decline to allow the intervention because all the water is already allocated.

Sketch of woman in glasses arguing at the podium.

Rita Maguire argues for Arizona. (William Hennessy)

Dvoretzky added that the United States asserted ownership and control over the Nation’s water rights at the outset of the Arizona case in 1952 — and still does. The United States recently asserted in a New Mexico water rights case that it remains “the legal owner” of all Navajo Nation water rights. Drawing from the federal government’s “bundle of sticks” metaphor, Dvoretzky argued that the Nation’s water rights property “stick” guaranteed by the treaty has been effectively confiscated by the United States for its own purposes since at least 1952. If that’s so, then the federal government by its actions has acknowledged an enforceable fiduciary duty. Whether that duty extends to the relief sought by the Nation would be resolved on remand.

Representing Arizona and other intervening states, Rita P. Maguire focused on defending the Law of the River, the legal regime governing rights to the current allocation of water from the Colorado River. Gorsuch attempted to establish that the states’ interests were limited to the allocation and not the Nation’s demand for an assessment and a plan.

Justices Samuel Alito and Brett Kavanaugh focused on the allocation question, asking a series of policy questions about the “real world” consequences of a victory here for the Nation. They suggested that the Nation could receive a windfall of water at the expense of Arizona and other states. The federal government agreed that all Colorado River water has been allocated and added that if the Navajo prevail, many other tribal nations would demand similar treatment. Dvoretzky reminded the justices that the question before the court in this case is not whether the government must give the Nation water from the Colorado, but only whether the United States must conduct an assessment and plan for the Nation’s water needs. In response to Alito’s concern about reallocating the water, the Nation stressed that its claims do not implicate, at this time or perhaps ever, the current allocation of the Colorado River.

Posted in Featured, Merits Cases

Cases: Arizona v. Navajo Nation

Comments